Climate Change and its Implications on Security in the Developing World

The evolving dynamics of climate change present some of the most wide-ranging and significant security challenges for organisations operating in many of the world's developing countries. Understanding where and how climate change will likely exacerbate already known threats, as well as exponentially produce new ones over time, means the imperative for organisations and risk management systems to adopt a proactive and adaptive posture could not be greater. As this insight report will outline, climate change is only set to push the drivers of insecurity at a new pace, triggering cycles of violence and crises within the most vulnerable nation-states, and with it further complicating the task of mitigating the risk to personnel and operations on the ground.

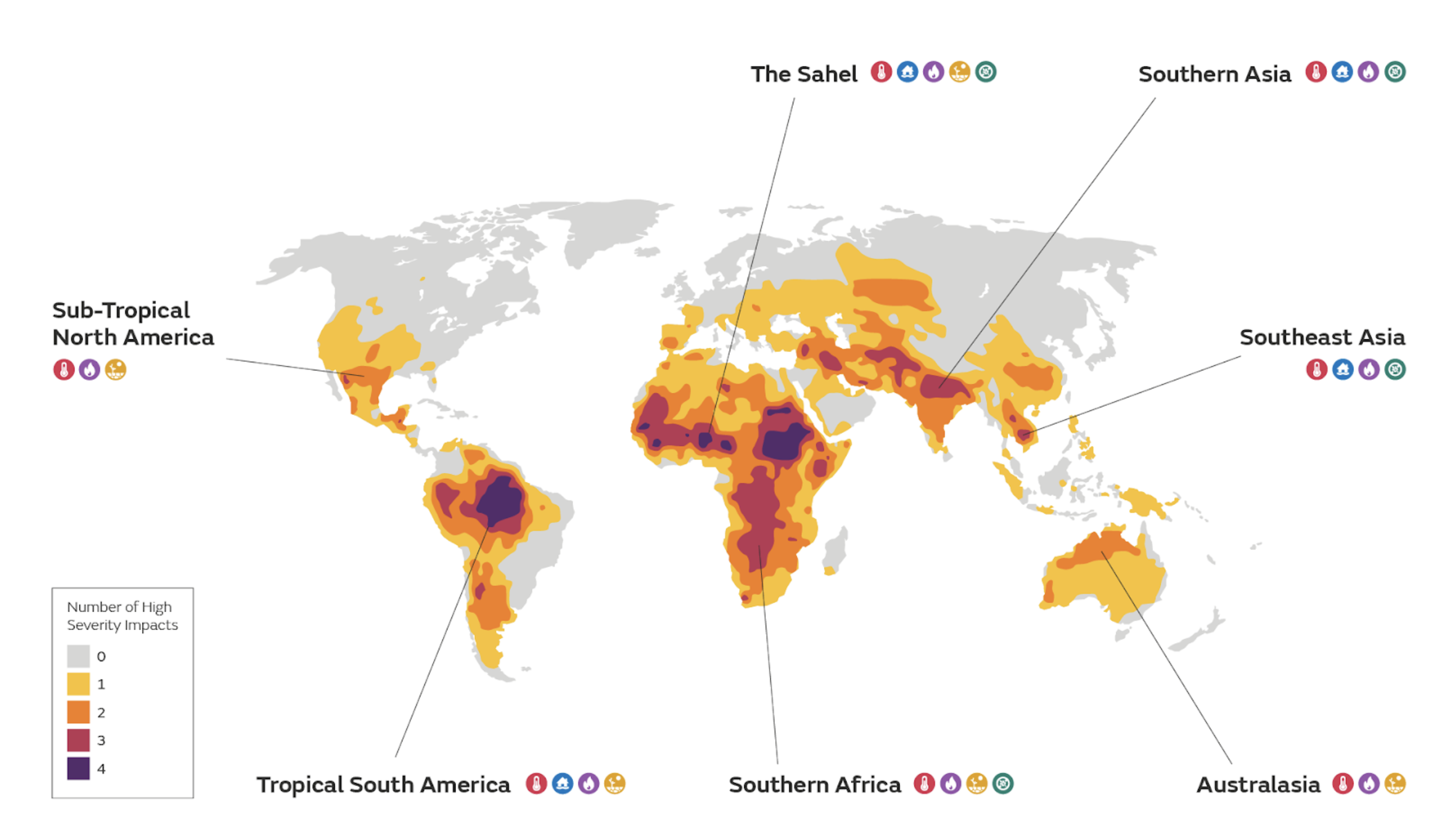

Figure 1 - Source: Met Office. (n.d.). Global impacts of climate change - projections. [online]

Aggravating Resource Scarcity

The growing scarcity of resources - brought on primarily by climate change directly and sometimes indirectly, as a result of climate change-induced migration - such as water, arable land, and fisheries is leading to increasingly fierce competition and conflict in many impoverished regions. Disputes over water resources have escalated into conflicts between different communities, as seen with the farmer-herder conflict across Nigeria where weekly incidents result in dozens killed. Similarly, reduced arable land availability, due to factors like desertification or flooding - which will be most severe in the Sahel, North Africa, Southern Asia, and Southeast Asia (see Figure 1) - can trigger land use and ownership disputes. In coastal regions, the depletion of fisheries can lead to economic strain and competition, heightening the potential for conflict and piracy for example.

For personnel operating in areas where resource scarcity is inducing tensions, it is only likely to produce ever more serious challenges and operational risks. Operational risks, such as restricted access to regions, confiscation of supplies, or hostility towards aid workers, will remain heightened in these environments. Security risks amplify, with personnel potentially facing increased targeted violence or incidental risk relating to resource-related conflicts. Additionally, engaging with communities under such stress can be challenging, especially if the organisations are perceived as exacerbating resource scarcity issues.

To mitigate these growing risks, organisations operating in regions suffering from aggravating resource scarcity should adopt a conflict-sensitive approach in their operations, understanding the nuances of how their activities intersect with local resource dynamics. Organisations should aim to strengthen their relationships with local community leaders and authorities to gain acceptance, as well as real-time insight into local security dynamics. Collaborating with local communities, governments, and other stakeholders is crucial in addressing resource scarcity and mitigating security risks.

Agricultural Economic Decline

The direct economic impact of climate change is substantial and multifaceted, a decline in agricultural output due to erratic weather patterns, droughts, or floods for example will directly affect the purchasing power of the majority, leading to reduced consumer spending. This contraction can lead to a slowdown in local retail and service sectors. Local retail and service industries, often the backbone of small-town economies, are highly sensitive to fluctuations in agricultural productivity. A poor harvest season can lead to reduced spending on non-essential goods and services, leading to lower revenues for businesses, as well as increased costs for food products, affecting the entire value chain up to the consumer. Economic contractions can have a cascading effect, impacting employment and income levels across whole communities and can and will escalate security risks, with economic hardship typically resulting in a rise in crime rates, protests, and internal conflicts, whilst also providing a boom of new recruits for active armed groups, inducing a cycle of violence that can be very difficult for a community to recover from.

Organisations with operations close to communities vulnerable to the worsening direct impacts of climate change should frequently review the local socio-economic and political landscape - which will often drive any increase in security risk rates - and adjust risk assessments and security protocols accordingly.

Climate-induced Conflict Risks on the Rise

Continued human demographic pressures, development, and ensuing resource scarcities brought on by climate change, is expected to result in ever more state mega projects aimed at remedying these trends. However, some of these mega projects are set to severely escalate tensions among several rivaling nations.

Unilateral exploitation often leads to the depletion or degradation of shared resources like water, minerals, and fossil fuels. This scarcity can lead to potential massive harmful impacts for countries that share the resource - a concern faced by Egypt and Sudan following the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on the River Nile, where several riparian countries are expected to face the highest number of high severity impacts exacerbated by climate change (see Figure 1) - and will become a direct cause of conflict for some, as these states compete for vital resources. Historical precedents demonstrate how resource scarcity can seriously escalate tensions, especially if the affected state perceives the degradation as an infringement on its sovereignty or a threat to its national security.

Unilateral exploitation projects can also lead to major economic disparities, particularly when one country benefits significantly at the expense of its neighbour. This inequality can breed resentment and mistrust, contributing to a hostile political climate that can ratchet up interstate tensions and fuel nationalist sentiments, particularly when they are perceived as aggressive or exploitative. Nationalism, in turn, can exacerbate political tensions and make diplomatic resolution more challenging. In response, states may engage in military posturing or arms races, significantly increasing the risk of conflict. This is particularly true in regions with existing geopolitical tensions or historical rivalries.

As inter-state conflict becomes evermore prevalent across the globe - driven also by multiple factors unrelated to climate change - risk managers must remain wary of the growing geopolitical risks that can result in diplomatic spats, embargoes, and conflict, triggering major operational pitfalls and security crises.

Weak Governance and State Fragility:

The direct consequences of climate-related events such as extreme weather, rising sea levels, and the resulting massive movements of populations not only exacerbate existing problems for many developing countries, but also create new challenges for their national governments, many of which will be incapable of effectively responding. As mentioned above, the impact on agriculture alone will likely be a major driver of instability and insecurity for many nations, as will resource scarcity, climate change-induced mass migration, and the enormous strain on government budgets - leading to increased public debt and heightening the risk of a sovereign debt crisis. Existing social and economic structures will be increasingly disrupted, with governments unlikely to respond fast enough to mitigate the dangerous repercussions, further eroding public trust in existing institutions or governments.

This erosion of trust creates power vacuums, which are routinely exploited by armed groups, further destabilizing regions and contributing to a cycle of fragility, insecurity, and rising tensions, that sometimes escalate into conflict or the emergence of ungoverned territory controlled by militant groups. All of which seriously complicate the security risk management of any international travel, development or investment projects further. Often when internal security and governance structures weaken a lot, it can lead to major shifts in government, with old political systems and players being driven out and replaced with something new, often no more effective than their predecessors - as seen across many Sahelian countries along the ‘Coup Belt’. For organisations planning to operate or already operating in fragile states, the collapse of existing governance structures will become increasingly common, and with it the need to better monitor these issues, anticipate the security challenges they bring, and mitigate the risks.

Conclusion

The multifaceted challenges posed by climate change, of which this insight has only briefly addressed a select few, will continue to significantly influence and accelerate the rate of change across many security landscapes, particularly in vulnerable regions. It demands risk managers inform themselves more regularly - especially when many security concerns are signposted long before they manifest into serious problematic issues on the ground - as part of an anticipatory security risk management strategy. By being proactive and adaptive in response to the increasingly fast evolving security landscape catalysed by climate change, organisations can simultaneously reduce costs and better ensure the safety of their people and assets in the long-term.